Introduction: Why do Manipulative Skills Still Matter?

In an era increasingly dominated by simulations and digital experimentation, manipulative skills—the physical and procedural competencies used in chemistry laboratories—remain indispensable. They refer to the coordinated actions students perform to handle apparatus, measure precisely, operate safely, and record observations accurately.

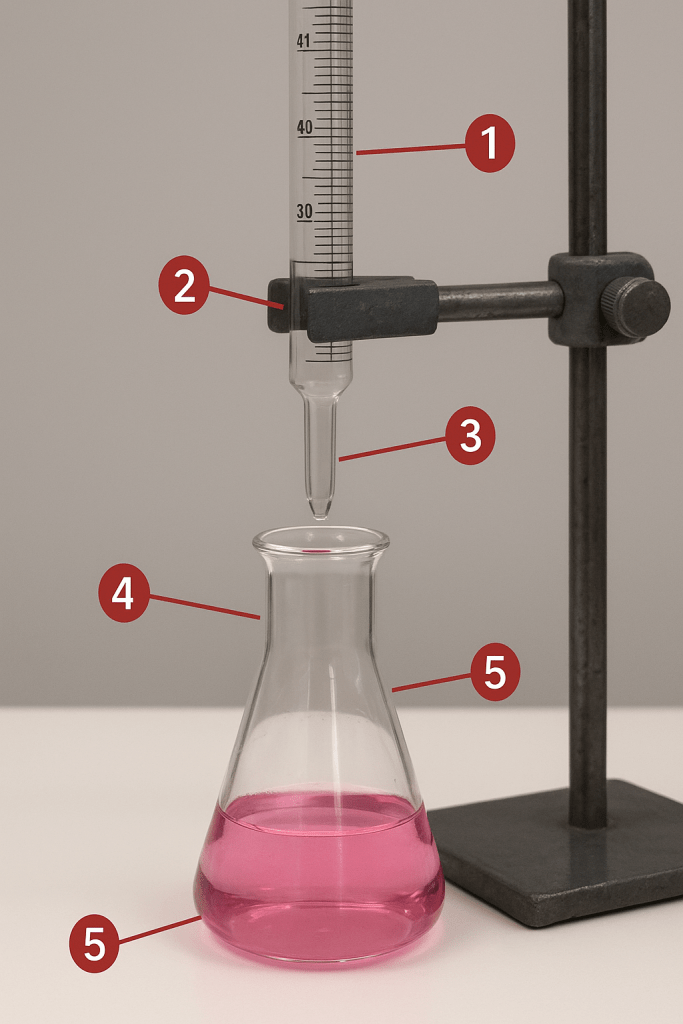

These are not merely “technical” skills. They are cognitive anchors that link hands-on practice with deep conceptual understanding. For instance, accurate titration techniques refine the understanding of stoichiometry, while precise thermal control illuminates the reaction kinetics (Moni et al., 2007). Research has consistently demonstrated that students who develop strong manipulative competence exhibit higher conceptual retention and scientific reasoning (Oliveira et al., 2023).

Characterising Manipulative Skills.

Manipulative skills in chemistry have several interconnected dimensions.

- Technical Precision: Accurate measurement, setup, and control of experimental variables.

- Safety and Risk Management: Consistent use of personal protective equipment, adherence to safety protocols, and awareness.

- Instrument Mastery: Confident operation and calibration of equipment such as burettes, pH meters, or data loggers.

- Observation and Sensory Awareness: Ability to detect colour changes, gas evolution, or temperature shifts.

- Recording and Data Fidelity: Systematic note-taking, uncertainty calculation, and clear data representation.

According to Moni et al. (2007), manipulative skills should be viewed as integrated competencies rather than discrete checklists. A competency-based approach allows teachers to assess how technique, observation, and reasoning work together to produce valid results, a principle now embraced by international exam boards such as Cambridge, Pearson Edexcel, Independent Examinations Board (IEB, RSA), and Zimsec, amongst others.

Pedagogical Role: The Practical Meets the Conceptual.

Hands-on skills are not merely an add-on to theory; they form a pedagogical bridge between knowledge and understanding.

- Concrete Experience Reinforces Abstract Thought

Laboratory practices transform abstract models into observable reality. For instance, equilibrium concepts become tangible when students watch colour changes or precipitate formations (Oliveira et al., 2023). Further transition chemistry concepts, such as ligand exchange, deprotonation, and redox, can be explained with such visuals. - Inquiry and Discovery

Inquiry-based practical work encourages students to hypothesise, test, and iterate, mirroring authentic scientific inquiry. Killpack and Melón (2020) found that scaffolded inquiry laboratories significantly improved experimental design and student confidence. Students may design an experiment in qualitative analysis where they plan to separate a mixture of two cations and an anion and predict the effect of a change in concentration on the rate of reaction starting from concentrated solutions. - Alignment with Exam Board Demands

Exam boards such as IAL, IAS, and Cambridge International embed manipulative competencies in practical endorsements or written papers. Teachers who intentionally align instruction with these objectives help students succeed, both practically and theoretically (Van Wyk et al., 2024). Students must always work with exemplar questions in practice.

Current Research on Manipulative Skills.

Contemporary research highlights several important trends.

- Integrated Skill Development: Practical work yields stronger learning gains when explicitly connected to conceptual instruction (Oliveira et al. 2023).

- Scaffolded Inquiry: Structured support during early laboratory tasks builds self-efficacy and the transferability of skills (Killpack & Melón, 2020).

- Competency-Based Assessment: Rubrics emphasising process and reflection outperform one-off “tick-box” practicals (Agustian et al., 2022).

- Equity Through Design: Gender-based performance gaps narrow significantly when laboratories encourage collaboration, equitable task allocation, and formative feedback (Odom et al. 2021).

Gender Disparities in Manipulative Skill Acquisition.

Although ability differences are negligible, research has identified contextual gender disparities in laboratory performance and confidence.

- Socialisation and Prior Experience: Boys may have more informal tinkering opportunities, while girls often face social barriers to hands-on participation (Miller et al., 2023). Fathers may have been aided more by boys than girls in servicing their cars or by fixing a malfunctioning bicycle axle.

- Confidence and Stereotype Threat: Females may underestimate their competence due to stereotype threat, particularly in co-educational lab settings (Odom et al., 2021).

- Teacher Bias and Role Allocation: Teachers may unconsciously assign complex apparatus tasks to male students, limiting practice opportunities for females (Oliveira et al. 2023).

However, when teachers intentionally rotate tasks, scaffold early experiences, and provide confidence-building feedback, these gaps disappear. Thus, gender disparities are less about innate differences and more about pedagogical and social designs.

Teachers’ Role: Practical and Inclusive Strategy.

1. Model and Scaffold Skills

Demonstrate precise techniques with explicit narration (“think aloud”) before the students attempt them. This approach reduces cognitive load and clarifies expectations (Killpack and Melón 2020). Students may practise titrations with water or old dilute solutions before actual practice.

2. Use Structured Progression

Start with guided practicals and then gradually withdraw support (beyond the Zone of Proximal Development). Scaffold fading promotes independence and transfer of learning.

3. Ensure Equitable Participation

Rotate roles in pair or group labs — apparatus setup, measurement, recording, and reporting — to provide every student equal technical exposure (Oliveira et al., 2023).

4. Adopt Competency-Based Assessment Rubrics

Assess accuracy, safety, and metacognition (why, not just how, a step is performed). Provide timely formative feedback to reinforce skill mastery (Agustian et al. 2022). Learners may also have the opportunity to evaluate each other in terms of their participation and contribution to the group.

5. Build Confidence Through Reflection

Encourage short post-lab reflections or video analyses where students evaluate their performance and errors. This fosters metacognitive awareness and ownership of improvements (Odom et al., 2021). The teacher may also ask the students to evaluate the experimental procedure in terms of improvement.

6. Link Labs to Curriculum Standards.

Align each practical activity with the IAL, IAS, or Cambridge assessment objectives to ensure relevance and exam readiness (Van Wyk et al., 2024). Students should always be shown the relevant typical examination questions and sometimes, the examiners’ reports.

Conclusion: Teaching the Hands, Training the Mind.

Manipulative skills are at the core of scientific literacy. They translate theory into tangible understanding, promote disciplined inquiry, and cultivate safety, precision, and reflection. When laboratories are structured around inclusive pedagogy, all students, regardless of their gender, can achieve mastery and confidence in practical chemistry.

The future of chemistry education lies not in replacing the bench with a screen but in integrating both intelligently. As we prepare learners for the demands of the 21st century, one truth remains constant: good chemistry begins with good hands.

Call to Action:

If you found this article valuable, subscribe for more research-grounded discussions on chemistry pedagogy and innovative teaching strategies.

References.

Agustian, H. Y., et al. (2022). Learning outcomes of university chemistry teaching in higher education: A systematic review. Review of Educational Research.

Killpack, T. L., & Melón, L. C. (2020). Increased scaffolding and inquiry in an introductory biology laboratory improves experimental design skills and scientific self-efficacy. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 19(3), ar35.

Moni, R. W., Hryciw, D. H., Poronnik, P., Lluka, L. J., & Moni, K. (2007). Assessing core manipulative skills in a large, first-year laboratory. Advances in Physiology Education 31(3), 228–232.

Odom et al. (2021). Meta-analysis of gender performance gaps in undergraduate STEM courses: patterns across biology and chemistry. CBE: Life Sciences Education.

Oliveira et al. (2023). Practical work in science education: A systematic literature review. Frontiers in Education, 8, 1151641.

Van Wyk, A. L., et al. (2024). Analysis of analytical chemistry laboratory experiments for adoption of inquiry-based approaches. Journal Chem. Educ.

Leave a comment