Dr Caleb Moyo

Introduction: When Chemistry Assumes a Perfect Vision.

Picture an A-level chemistry practical: a student peers intently at a burette, waiting for the solution to turn pink. The teacher says, “You’ll know it when you see it.” This is true for many students. For others, it is not a matter of attention or ability; it is biology.

Colour blindness, more accurately termed colour vision deficiency (CVD), is a largely invisible factor in chemistry education. It rarely features in curriculum documents, is seldom discussed in teacher training, and is often mistaken for carelessness when manifested in assessments. However, chemistry, more than many other school subjects, is deeply colour-dependent. Ignoring this reality is not a tradition; it is an oversight.

This article examines the theoretical basis of colour blindness, reviews peer-reviewed research on its educational impact, and offers evidence-based curriculum and teaching adjustments for A-level chemistry education. The conclusion is simple but uncomfortable: when chemistry teaching relies uncritically on colour, some students are disadvantaged before the lesson even begins.

1. Theoretical Foundation of Colour Blindness.

What Is Colour Blindness?

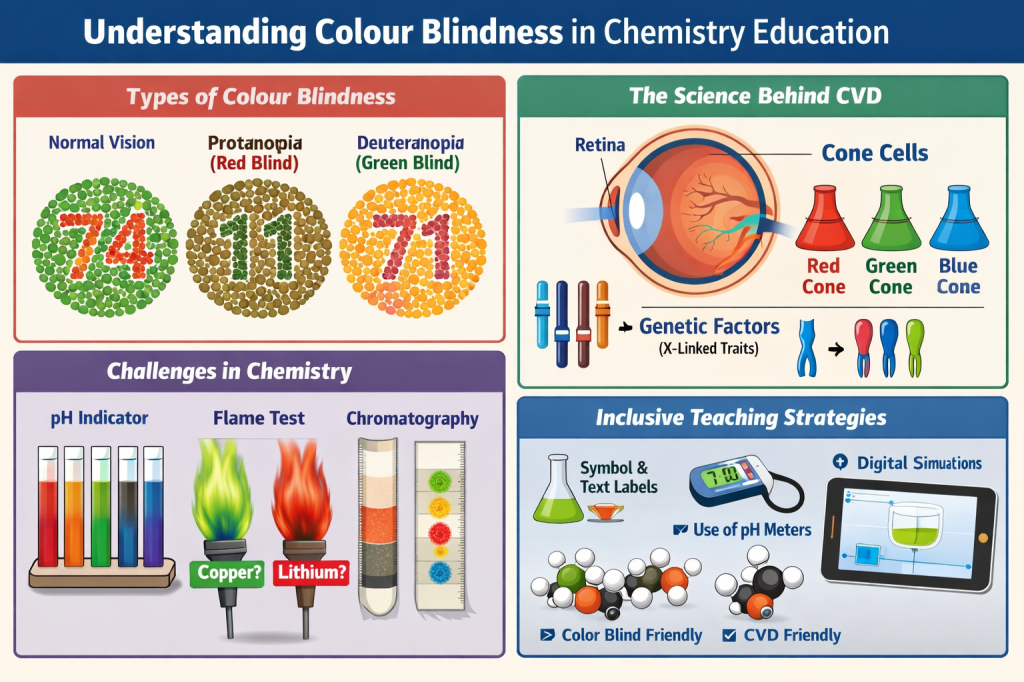

Colour blindness, or colour vision deficiency, refers to a reduced or altered ability to perceive differences between certain colours. It is not the inability to see colour altogether, a persistent myth that refuses to die. Most individuals with CVD perceive colour differently.

Human colour vision depends on three types of cone photoreceptors in the retina that are sensitive to long (red), medium (green), and short (blue) wavelengths of light. Normal trichromatic vision arises from the combined activities of these cones. Colour vision deficiency occurs when one or more cone types are absent, malfunctioning, or spectrally shifted (Goldstein, 2014).

Types of Colour Vision Deficiency

The most common forms include

- Deuteranomaly / Deuteranopia (green-weak or green-blind)

- Protanomaly / Protanopia (red-weak or red-blind)

- Tritanopia (blue-yellow deficiency, rare)

Red–green deficiencies account for the vast majority of cases and are typically X-linked genetic conditions, making them far more prevalent in males (approximately 8%) than in females (around 0.5%) (Birch, 2012).

Why Does This Matter in Chemistry?

Chemistry instruction frequently assumes reliable colour discrimination: indicators, flame tests, transition metal complexes, chromatograms, energy diagrams, and redox reactions all depend on colour cues. From a cognitive perspective, this means that students with CVD must engage in compensatory processing, increasing their cognitive load for tasks that their peers complete automatically (Sweller, 2011). This is not academic rigour; it is a poor design.

2. Research Grounding: What the Evidence Says.

Prevalence and Educational Blind Spots.

Multiple studies have confirmed that a significant minority of students in secondary science classrooms have undiagnosed colour vision deficiency (Cole, 2004; Spalding, 1999). Alarmingly, many students are unaware of their condition until confronted with persistent difficulties in practical science tasks.

In chemistry-specific contexts, research published in the Journal of Chemical Education highlights that colour-blind learners struggle disproportionately with the following:

- Acid–base titration endpoints

- Interpreting colour-coded graphs and spectra

- Identifying precipitates and flame test colours

- Reading chromatography results

(Hansen et al., 2020)

These difficulties are non-trivial. They affect both formative learning and summative assessment, especially in high-stakes A-level exams.

Misinterpretation as Low Ability.

One of the more troubling findings in the literature is that colour-blind students are often perceived as careless or conceptually weak rather than perceptually disadvantaged (Olson & Brewer, 1997). This misattribution undermines confidence and participation—two variables that strongly correlate with achievement in science.

3. Curriculum and Teaching Adjustments: Designing Chemistry for All Eyes.

The solution is not to “lower standards” but to design smarter. Inclusive chemistry teaching benefits everyone, not just students with CVD.

Curriculum Design Adjustments

- Reduce colour-only coding in diagrams, graphs, and reaction schemes

- Pair colour with symbols, labels, patterns, or line styles

- Ensure textbooks and slides use colour-blind-safe palettes (e.g., blue–orange rather than red–green)

Research shows that dual coding—combining visual cues with text or symbols—improves comprehension for all learners (Mayer 2020).

Inclusive Laboratory Practices.

- Teach titrations using pH meters or conductivity probes alongside indicators

- Allow students to verify colour changes collaboratively

- Explicitly teach what the colour change represents chemically, not just that it occurs

Good chemistry teaching explains mechanisms; bad teaching points at colours and hopes for the best.

Assessment Accommodations.

- Avoid assessment items where colour is the sole discriminating variable

- Provide alternative data representations in practical exams

- Ensure that access arrangements align with fairness, not advantage.

International examination boards increasingly acknowledge this need, although implementation remains uneven.

Use of Technology.

Digital simulations, spectroscopy software, and data-logging tools can decouple understanding from colour perception. When used thoughtfully, technology supports the Universal Design for Learning (UDL) by offering multiple means of representation (CAST, 2018).

4. Impact on Student Performance: The Quiet Inequality.

Conceptual Understanding.

When a learner misreads a colour change, the error is often recorded as a conceptual misunderstanding. In reality, the concept may be intact, but the perception is not. Over time, repeated “mistakes” erode students’ confidence and discourage persistence in chemistry pathways.

Practical Accuracy and Assessment Outcomes.

Consider a student who consistently overshoots titration endpoints or misidentifies transition metal colours during a titration. In an A-level system, where precision is rewarded, such errors accumulate. Research indicates that colour-dependent practical tasks can systematically depress the scores of students with CVD (Hansen et al., 2020).

Participation and Identity.

Perhaps the most damaging effect is on the science identity. Students who feel “bad at practical chemistry” are less likely to pursue chemistry, regardless of their theoretical aptitude. This is not a talent pipeline problem; it is an access problem.

Conclusion: Chemistry Must Learn to See Differently.

Colour blindness in A-level chemistry is not rare, trivial, or the learner’s fault. This interaction between human biology and curriculum design is predictable. The good news? It is also fixable.

By grounding chemistry teaching in evidence, inclusive design principles, and professional honesty, educators can ensure that success in chemistry depends on understanding reactions, not guessing colours. The call to action is clear: audit your materials, rethink your practicals, and teach chemistry in a way that all capable minds can access it.

Ultimately, chemistry involves transformation. It would be ironic if the discipline itself refused to change.

References

Birch, J. (2012). Worldwide prevalence of red–green color deficiency. Journal of the Optical Society of America A, 29(3), 313–320.

CAST. (2018). Universal Design for Learning Guidelines version 2.2.

Cole, B. L. (2004). The handicap of abnormal colour vision. Clinical and Experimental Optometry, 87(4–5), 258–275.

Goldstein, E. B. (2014). Sensation and perception (9th ed.). Cengage Learning.

Hansen, A., Carter, C., & Pritchard, D. (2020). Color vision deficiency and chemistry education. Journal of Chemical Education, 97(8), 2301–2308.

Mayer, R. E. (2020). Multimedia learning (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Olson, J. M., & Brewer, W. F. (1997). Misattribution of perceptual errors. Cognitive Psychology, 33(1), 1–38.

Spalding, J. A. (1999). Confessions of a colour blind painter. British Medical Journal, 319, 860–863.

Sweller, J. (2011). Cognitive load theory. Psychology of Learning and Motivation, 55, 37–76.

Leave a comment