Dr Caleb Moyo.

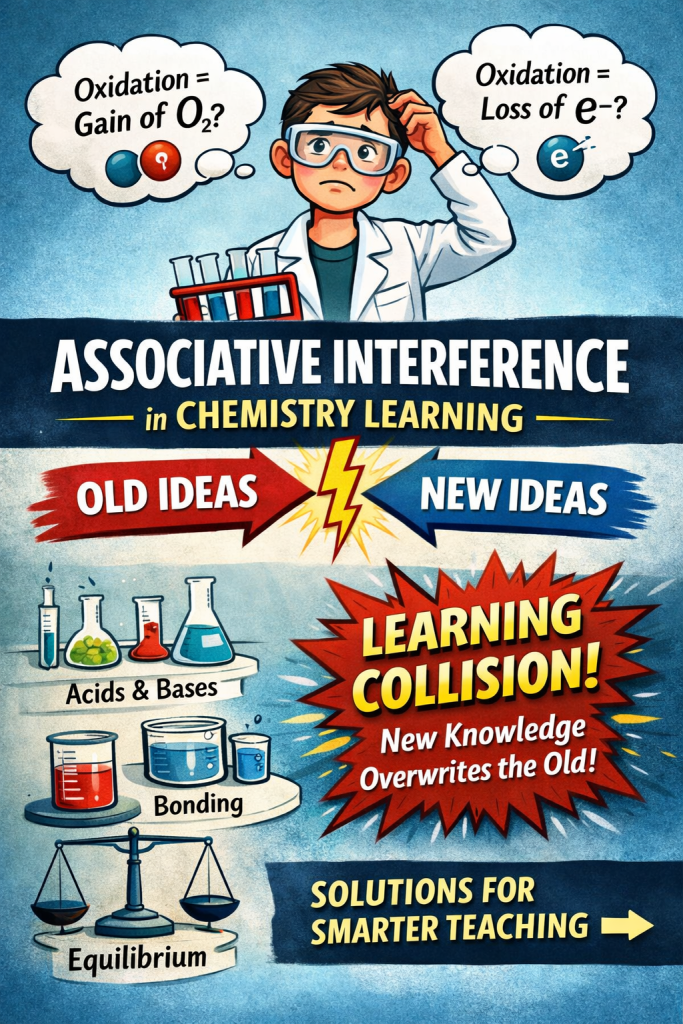

If you have ever asked a student to explain acids, ionic bonding, redox, and equilibrium—and received four incompatible answers–you have met a friendly cognitive assassin: associative interference. This subtle psychological phenomenon quietly corrodes student understanding, not because learners are lazy or unintelligent but because human memory does not segregate knowledge neatly by textbook chapter headings. Instead, learning is a competitive sport among networks of associations, and chemistry concepts often bid on the same retrieval cues, making confusion almost inevitable without deliberate instructional design (Anderson, 2000; Baddeley, 2012; Chi, 2013);

In this article, we unpack what associative interference is, why chemistry invites it, where it shows up in canonical failure points, how common teaching practices can unintentionally amplify it, and—most importantly—how evidence‐based instructional strategies can mitigate its effects.

What Is Associative Interference? An Elegant Cognitive Tug-of-War

Memory does not function like a neatly indexed textbook does. Instead, human memory stores information in networks of associations activated by retrieval cues, such as words, symbols, contexts, or sensory triggers (Anderson, 2000; Baddeley, 2012). When multiple concepts share similar cues, they compete for access, leading to proactive interference (old knowledge blocking the new) or retroactive interference (new knowledge obscuring the old) (Anderson, 2000; Baddeley, 2012);

For example, students might first learn that oxidation involves the gain of oxygen in the context of combustion. Later, when they learn that oxidation means losing electrons in redox chemistry, both meanings hinge on the cue “oxidation.” Without explicit discrimination between these definitions, students often combine them into a hybrid belief that conflates both meanings—scientifically incorrect yet cognitively understandable because their memory retrieval cues overlap (Chi, 2013).

This is why a student may confidently assert the following:

“Oxidation always involves oxygen,” even after lessons on electron transfer. Such responses are not signs of intellectual failure; they illustrate how competing associations can quietly win in the cognitive marketplace when instructions do not deliberately separate them.

Why is Chemistry Especially Vulnerable to Interference?

Chemistry is modular in textbooks but interdependent in terms of cognition. Many fundamental concepts exist in networks of relationships, not in isolated islands. The dreaded symbol e⁻, for example, serves multiple conceptual masters.

- In atomic structure: a particle with negative charge

- In bonding: something shared (covalent)

- In redox: something transferred

- In electrochemistry: something that flows

Unless a lesson explicitly demarcates these roles, students treat “electron” as one entity with one meaning, leading to interference (Chi, 2013).

This difficulty is exacerbated by Johnstone’s triangle, which refers to the need for students to simultaneously navigate and coordinate macroscopic observations, symbolic representations, and submicroscopic mental models (Johnstone, 1993). Cognitive load theory suggests that when too many interacting elements must be processed simultaneously, learners default to surface cues rather than deep principles (Sweller, 2011). Chemistry, with its layers of abstraction and symbolism, is therefore not just difficult —it is cognitively dense and interference-prone by design.

Interference in Action: Where Things Break Down in Chemistry Learning.

The impact of associative interference becomes most visible at classic failure points:

Bonding

Students often learn about ionic bonding as electron transfer and later about covalent bonding as electron sharing. When these explanations live in the same cognitive space without contrast, students may conclude that:

“All bonds transfer some electrons.”

This hybrid misunderstanding arises not from ignorance but from shared memory cues that were never properly differentiated (Taber, 2014).

Acids and Bases

The Arrhenius, Brønsted–Lowry, and Lewis definitions describe acids and bases, but they emphasize different processes (H⁺ production, proton donation, and electron pair acceptance, respectively). Without explicit contrast, students often blend these definitions, producing statements such as the following:

“An acid donates protons and accepts electrons.”

This is neither Arrhenius nor Lewis nor Brønsted; yet, it is cognitively plausible when multiple meanings attach to the single cue “acid” (Chi, 2013; Lowery Bretz & McClary, 2018).

Redox

Definitions such as “oxidation = loss of electrons” and “oxidation = gain of oxygen” compete for the same label. In the absence of clear instructional boundary setting, students can conflate them, especially in reactions where oxygen is not involved.

Equilibrium

The everyday meaning of “balance” (equal amounts) competes with the scientific meaning of the dynamic balance of rates. Students frequently believe that:

“At equilibrium, reactants and products are present in equal amounts,”

This is a misapplication of a familiar word to a new disciplinary meaning (Johnstone, 1993).

Energetics

Students often misinterpret exothermic and endothermic descriptors because they associate heat with activity rather than with the energy flow between the system and surroundings. This semantic interference leads to persistent errors.

These error structures are not anecdotal in nature. Educational research confirms that students produce systematic misinterpretations that align with interference patterns rather than random guessing (Chi, 2013; Taber, 2014).

Why Traditional Teaching Can Make Interference Worse

Ironically, many conventional instructional practices inadvertently amplify associative interference.

- Spiral curricula revisit the same terms across topics without explicitly delineating where one meaning ends and the other begins. Students revisit cues but not in ways that clarify competing meanings (Taber, 2014).

- Worked examples can increase procedural fluency while leaving conceptual networks tangled below the surface. Students may balance equations or compute pH values accurately without resolving the underlying conceptual associations.

- Massed practice (intensive teaching of a topic, followed by moving on to the next topic) encourages cue saturation. When related concepts are taught in immediate succession, such as kinetics immediately before equilibrium, students are more likely to fold one set of associations into the other, increasing interference (Sweller, 2011).

Teachers often strive for coherence by clustering related topics; however, without deliberate spacing, this can blur conceptual boundaries, instead of strengthening them.

What Research Says About Reducing Interference

The good news is that educational research offers tested instructional strategies that align with how human memory actually works.

1. Contrast Sets

Presenting similar concepts side by side and explicitly highlighting their differences helps learners form distinct memory cues for each idea. For example, contrasting bonding types (ionic, covalent polar, covalent non-polar) side by side with explicit prompts about what is not happening helps separate associations (Chi, 2013).

2. Boundary Training

Teach students when a rule does not apply to a particular situation. Ask, for instance:

“When does increasing concentration not increase yield?”

This prompts students to recognise limitations and prevents rule overgeneralisation.

3. Spaced Retrieval

Instead of massing related topics together, revisit earlier concepts interleaved with new topics. For example, equilibrium concepts can be revisited after kinetics and thermodynamics lessons. This strategically spaced retrieval strengthens discrimination and reduces retroactive interference (Roediger and Karpicke, 2006). It also mitigates the risk of collapse between closely linked topics, such as kinetics and equilibrium.

4. Error-Focused Reflection

When students articulate why a misconception is wrong—rather than simply correcting the record—they engage in deeper processing that weakens the interfering association and strengthens the correct one (Chi, 2013; Taber, 2014).

5. Diagnostic and Constructed Assessments

Multiple-choice questions can mask interference because students may guess the correct answer for the wrong reasons. Constructed responses and concept inventories reveal whether students have resolved conflicting associations (Cooper et al., 2013).

Assessment and Technology: A Fresh Angle

Traditional assessments frequently focus on what students know rather than how they know it, which can conceal interference-driven mistakes. Modern diagnostic tools and adaptive learning platforms can highlight patterns of misunderstanding by clustering students’ responses that reflect particular interference structures. This enables targeted remediation, which is rooted in cognitive science.

Why Interference Matters for Equity and Inclusion

Associative interference does not affect all students equally. Learners who depend more heavily on contextual or linguistic cues—such as English-language learners, neurodivergent students, and those with sensory processing differences—are especially vulnerable when educational contexts do not explicitly separate overlapping meanings. These are cognitive accessibility issues, rather than ability issues.

Conclusion: A Respectful Challenge to Chemistry Instruction

Chemistry does not need to be harder; it needs to be taught more intelligently. Associative interference is not a mysterious aberration; it is a predictable outcome of how memory works when overlapping associations are left unchecked. By embracing instructional strategies grounded in research on human cognition, educators can help students build distinct, stable, and transferable conceptual networks in their minds.

The solution is not more repetitions of content but a better structural design of learning paths that manage cognitive interference rather than invite it.

References.

Anderson, J. R. (2000). Learning and Memory: An Integrated Approach. Wiley.

Baddeley, A. (2012). Working Memory: Theories, Models, and Controversies. Annual Review of Psychology.

Chi, M. T. H. (2013). Two Kinds and Four Sub-Types of Misconceived Knowledge: Ways to Change Them. In the International Handbook of Research on Conceptual Change. PDF at the Arizona State University:

https://education.asu.edu/lcl/publications/chi-m-t-h-2013-two-kinds-and-four-sub-types-misconceived-knowledge-ways-change-it

Cooper M. M., Underwood S. M., Hilley C. Z. (2013). Development and validation of the Mechanism Concept Inventory. Journal of Chemical Education.

Johnstone, A. H. (1993). The development of chemistry teaching: A cognitive perspective. Journal of Chemical Education.

Lowery Bretz, S. L., & McClary, L. (2018). Students’ Understanding of Acid Strength. Accessible PDF:

https://pendidikankimia.walisongo.ac.id/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/4.pdf

Roediger, H. L., & Karpicke, J. D. (2006). The critical role of retrieval practice in long-term retention (Testing Effect). Summary:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Testing_effect

Sweller, J. (2011). Cognitive Load Theory. Psychology of Learning and Motivation: Vol.

Taber, K. S. (2014). Chemical Misconceptions: Prevention, Diagnosis and Cure. Royal Society of Chemistry.

Leave a comment